No products in the cart.

Ordinary people who did something Extraordinary in life, read their success story!

Indian Brain built Rs 30 cr empire with a small initial investment, read his story

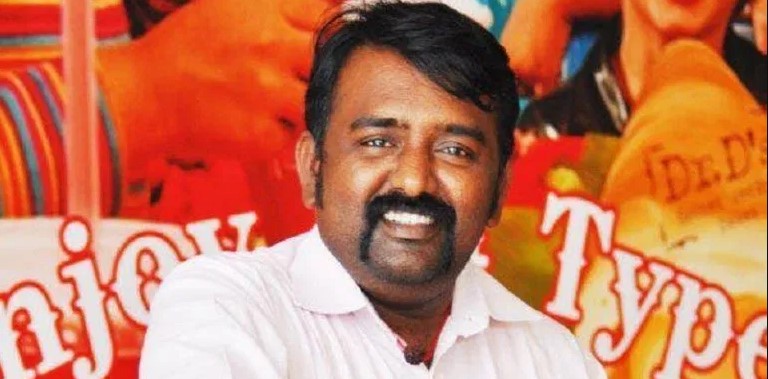

There is nobody in this world who wants to lead a frugal life. Though we all dream of being successful very few of us actually get to relish the taste of success. Many of them give up dreams midway due to lack of perseverance or loss at some point or some distractions. But none of these negative factors defeated Prem Ganapathy as he pushed himself to do better and hence he succeeded in becoming a great Indian entrepreneur and businessman.

Today, he is the founder of the restaurant chain Dosa Plaza. With a meagre initial investment of just Rs.100, he expanded Dosa plaza into a broad spectrum of a restaurant chain with 45 outlets in India, New Zealand, Oman, and UAE. Above all, he is a good human being.

He was born in Nagalapuram in Thoothukudi district of Tamil Nadu. He completed class X following which he left for Chennai to find himself a job. He then did multiple jobs in Chennai before going to Mumbai in 1990. He was stranded there with no money and no idea of the local language. However, he started working in a bakery with the help of a Tamil family.

After gaining some healthy knowledge and experience in this field, Ganapathy made up his mind to stand on his own legs. So, he started his own food business in 1992, selling idlis and dosas in a handcart opposite the Vashi railway station.

Five years later, he rented a shop and started experimenting with different varieties of dosas and in 2003, he launched his first outlet in a mall in Center One Mall at Vashi. In 2012, Dosa plaza has 45 branches in 4 countries serving more than 100 varieties of dosas. This is called the true meaning of ‘Success’

Even as Ganapathy faced ups and downs in his life, he was determined to do something on his own. He shared his experience in the initial stages of his life in Mumbai. What started as a bad start turned out to be an extraordinary journey for him.

“I was lured to Mumbai, only to be robbed. It was an inauspicious start to my entrepreneurial journey, but it turned out for the best.

I belonged to a poor family from Nagalapuram in Tamil Nadu’s Tuticorin district and had to abandon my dreams of higher studies to support my parents and seven siblings. I headed for Chennai, but only managed odd jobs, which fetched around Rs 250 a month that I’d send back home.

One day, an acquaintance offered me a job promising a salary of Rs 1,200 per month in Mumbai. I knew my parents would never approve of my decision to shift base, so I left for Mumbai without informing them. It was 1990 and I was just 17 years old. The acquaintance robbed me off the Rs 200 I had, leaving me stranded at Bandra.

I hardly understood the language and did not know anyone in the city, but returning wasn’t an option since I was penniless. So I did the only thing I could: I decided to stay on and try my luck.

The very next day I got a job washing dishes at a local bakery at Mahim for a salary of Rs 150 a month. The good bit was that I could sleep at the bakery itself. In the next two years, I picked up odd jobs at various restaurants and tried to save as much as possible.

In 1992, I managed to save up enough to start my own food business, selling idlis and dosas. I rented a handcart for about Rs 150 and ploughed in another Rs 1,000 to buy utensils, a stove and basic ingredients, and set up shop on the street opposite the Vashi train station,” he added.

“The same year, I brought in two of my brothers, Murugan and Paramashivan, who were younger than me by two and four years, respectively, to help with the business. We were very particular about quality and cleanliness, and unlike the people running other roadside eateries, we were very well-dressed and wore caps.

I got the recipes for dosas and the sambhar from my native place, which attracted a lot of customers. Soon enough, the business was booming and we were generating a net profit of around Rs 20,000 every month.

We even managed to rent out a small space at Vashi, which doubled as our living quarters and a makeshift kitchen, where we would prepare all the ingredients and masala every day.

However, it wasn’t smooth sailing. We faced the risk of the cart being seized by the municipal authorities as handcart food stalls do not get licences to ply their trade.

In fact, our cart was seized several times and I had to pay a fine to have it released. Thankfully, the harassment ended when we saved enough to open a restaurant.

In 1997, we leased a small space in the same locality by paying a deposit of Rs 50,000 and named it Prem Sagar Dosa Plaza. We paid a monthly rental of Rs 5,000 and also hired two people.

The restaurant was frequented by college-goers, some of whom became good friends. They taught me how to use the Internet, which helped me get new recipes from across the world. Soon, I began to experiment with dosas, rolling out offerings, such as the schezwan dosa, paneer chilly, and spring roll dosa. In the first year, we introduced 26 innovative dosas.

By 2002, we had managed to create more than 105 dosa varieties and our outlet had become very popular. However, I dreamt of opening a shop in a mall and even tried to get a place in some of the suburban malls. I was repeatedly turned down as space was reserved for branded eateries like McDonald’s and Pizza Hut.

My luck turned the day Centre One mall decided to open up in our vicinity. Its management team and staffers had often dined at our restaurant and enjoyed our fare. They suggested that we set up an outlet in the mall and we happily complied.

Our dosas won us publicity and people began approaching us with franchise requests. We agreed, with the stipulation that we would supply the dosa batter and other ingredients. The first franchise outlet opened at Wonder Mall in Thane, in 2003. Around 4-5 years ago, we got a new brand logo, Dr D.

We’ve been getting several requests from people who want to set up Dosa Plaza outlets in other countries. We have three outlets in New Zealand, two in Dubai and are looking at opening some in Muscat this year, along with 10-15 more restaurants in India.

These will add to our current tally of 43 (including franchisees) across 11 states. The business I started with a seed capital of Rs 1,000 has grown into a Rs 30 crore company and we are aiming for a Rs 40 crore revenue for this year,” he was quoted as saying by Economic Times.

Kachori seller’s annual turnover will shock you, earns more than Doctors, Engineers

Selling kachoris is a form of employment and it is far better than being unemployed. People might think kachori seller hardly making some money but the reality is that he is making more money than the professional engineers and doctors. After reading this, people might consider opening a store to sell kachoris in their free time.

Do you know much does an average Kachori seller earn annually? lakhs! Yes, you read it right. However, in a strange turn of events, GST officials had once raided a shop selling Kachoris in Aligarh and learnt that the kachori owner had an annual income of Rs 60-70 lakhs.

The shop owner by the name of Mukesh Kumar has been running his small shop for more than 10-12 years in Aligarh. During the raid operation, Mukesh reportedly revealed details about his daily income, expenditure including a number of people working under him and based on the data, they calculated his annual turnover which is expected to be around Rs 70 lakh.

They also learnt that Kumar despite his high annual income did not have a GST registration. As per the GST Council notification, any business with an annual turnover of Rs 40 lakh is liable to pay Goods and Services Tax. The officials also added that as per rules the kachori seller is liable to pay 5% GST, which is levied on the food items. So, he will now have to pay an annual tax of Rs 3.5 lakh.

Kumar who said ‘yes’ to get a GST registration claimed that he was totally not aware of the rules. “I am not aware of all this. I have been running my shop for the past 12 years and no one ever told me that these formalities are needed. We are simple people who sell ‘kachoris’ and ‘samosas’ for a living,” Kumar told IANS.

After Kumar’s case, officials now start believing that there could be more such sellers in the city making even higher incomes but getting away with the tax.

This man quit his job at Google to sell Samosas, his company turnover expected to touch 5 crores

Everyone wishes to do their dream job. There is no one who wants to do a job which they are not interested in. Though we all dream of getting a job in a reputed company, very few of us actually get the offer because they push themselves beyond boundaries to accomplish their mission. Their ability to look at life with a fresh and positive perspective makes them a class apart.

Getting a job at Google is no small feat for most aspiring IT geeks. Life is settled when you get a job at Google. The company offers a handsome paycheck. You can take pride in being part of a multinational giant company. But have you ever heard of a guy quitting a high-paying job at Google to sell samosas? Quite shocking, isn’t it? But for Munaf Kapadia, he just had to quit the job in a bid to follow his passion.

To quit Google company for the sole purpose of selling samosas might be a stupid idea for others but not for Munaf Kapadia who followed his heart. Today, his business has a yearly turnover of Rs. 50 lakhs. He is now the proud owner of The Bohri Kitchen (TBK) in Mumbai.

Munaf did what he felt was right. He completed his MBA from Mumbai’s Narsee Monjee Institute a few years ago. He was then employed by Google. He started his venture at Google working abroad. However, after a few years, he looked at life from a different perspective. He decided to start a business on his own and so he returned to his motherland India.

Munaf’s mother Nafisa always had an eye for cooking. She is fond of watching cooking shows on television and is a great cook. He was taken with the idea of opening a food chain after picking up some important tips from his mother. Initially, he let a few people sample his mother’s spicy food. Gradually, The Bohri Kitchen started to gain a lot of customers.

There is a huge demand for TBK’s samosas among iconic celebrities and five-star hotels. Apart from samosas, Nargis, kebab, Dabba gosht and many other spicy recipes are being sold here. The idea to invite people over for a paid meal was a hit and that’s how The Bohri Kitchen, a concept food dining experience in Mumbai, was born.

There is a demand for TBK’s samosas among famous celebrities and five-star hotels. The company now has a turnover of Rs 50 lakh and it is expected to reach greater heights in the times to come. Munaf, the ambitious guy aims to expand and increase the yearly turnover to nearly Rs 5 crore in the coming years.

From letting people taste samples to making the people wait in long queues to get the samosas, Munaf’s TBK gained good recognition. Munaf couldn’t have asked for a better result and he credited his historic success to his mother. He was featured in the Forbes Under 30 list.

After losing his job in the recession, he started a vada pav business, earns 4.4 crores

When the recession struck the UK in 2009, people were forced to quit their jobs and Sujay Sohani was one among them who faced this terrible experience. Due to these circumstances that put him on the back foot, he didn’t go into a shell, usually cursing his fate because he has always thought there is life even after disappointments. He didn’t lose hope. He met his friend Subodh Joshi.

Both of them made up their minds and decided to start the new phase of life by selling their hometown Mumbai’s popular delicacy, “vada pav”, in London. Today, their annual earning is somewhere around Rs.4.4 crore. Their success story is an inspiration for those who lose their jobs and think that there is no life after failure.

Sujay Sohani made to rejuvenate his lost self by building a better self in all aspects. The duo turned the tides to secure their lives ever so well as they escalated from lows of disappointment to highs of development.

Sujay previously plied his trade as the food and beverage manager at a London five-star hotel. Sujay who share a great deal of camaraderie with Subodh became friends in 1999 when they were studying at Rizvi College, Mumbai.

They have always been in touch and contacting each other over the years. It was when Sujay lost his job after the recession hit the UK, he shared his unfortunate experience with his friend Subodh, telling him how he was so let down and heartbroken after losing his job.

It was only after their conversation, an idea sparked by their beautiful venture. On August 15, 2010, they resolved to make money for a living by launching their vada pav business, identified as Shree Krishna Vada Pav, at Hounslow High Street.

When both were about to start the business, they found it a tad difficult to find a perfect place to set up their stall. At the start, it was a Polish ice cream café owner who allowed the two of them to take someplace for their new venture. The rent was Rs 35,000 and both found it hard to make or arrange money initially due to the financial crunch.

When the journey started, they sold the vada pav at £1 (Rs 80) and dabeli at £1.50 (Rs 131). To draw some attention to this new delicacy in London, they distributed vada pav to the random passerby for absolutely free.

From arranging money for rent to amplifying their business, they have come a long way to accomplish their task and today, their business expanded very well to wide spectrums as their annual turnover is now close to Rs 4.4 crores.

The stall is now the centre of attraction with up to 60 varieties of Indian dishes available on their menu. This is called success. Let’s share their success story to inspire other youths of the nation.